Let’s talk bits —and what bits REALLY do. If your horse is tossing their head, going behind the vertical, or dragging you like a sled dog, it might not be a training problem. It could be the metal in their mouth. This video breaks down how different bits work on both the outside and the inside of your horse’s head, and how those effects relate to their behavior — so you can choose the right bit for your horse and stop the guessing game.

What Bits Really Do: Outside Anatomy – How the Bit Connects

The bit doesn’t just sit in the mouth. It’s connected to the entire head via the bridle and reins. This includes the:

– Lips and corners of the mouth (commissures)

– Cheeks (which some cheekpieces push into)

– Poll (top of the head – leverage bits act here)

– Chin groove (engaged by curb chains)

– Nose (in bitless setups)

When you engage the reins, pressure doesn’t just act on the mouth—it radiates through the head. That’s why poll-sensitive horses may react strongly to leverage bits.

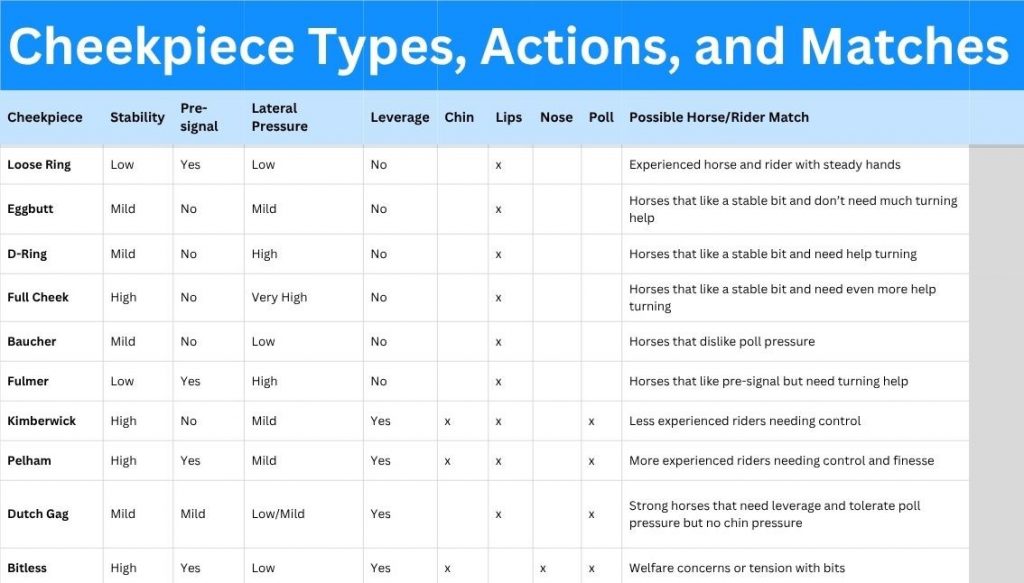

Pre-signal vs Stability

Pre-signal refers to the very first movement or shift a bit makes before actual pressure is applied.

It’s the horse’s early warning system. Horses are super sensitive to tiny changes in pressure, movement, and feel. A bit with good pre-signal gives the horse a chance to respond voluntarily before the rein aid escalates into actual leverage or pressure.

It’s like getting a yellow light before the red—more time to make a smooth decision.

A Stable Bit Is Like Riding in a Car with Good Suspension

It doesn’t move much. It just sits there until something intentional happens.

Horses who prefer this:

- Are young, green, or anxious

- Have had inconsistent or unclear hands

- Get nervous with too much movement in their mouth

- Are heavy or desensitized and just want clarity, not chit-chat

A stable bit gives predictability. The signal doesn’t change unless the rider really means it.

A Pre-Signal Bit Is Like Riding with a Sensitive Dance Partner

It moves and shifts with every little rein motion. Great for:

- Trained, sensitive, or finessed horses

- Horses used to subtle communication

- Riders with steady, independent hands

But if the rider’s hands are noisy, heavy, or inconsistent, a pre-signal bit becomes a nagging, confusing, anxiety-inducing nightmare.

| Horse Type | Prefers Stability Because… |

|---|---|

| Young/insecure | Too much motion = overstimulation |

| Hard-mouthed | Needs clear ON/OFF signals |

| Nervous/resistant | Finds movement unsettling or distracting |

| Rider has unsteady hands | Bit movement = accidental micromanagement |

Example:

- A young OTTB might hate a loose ring snaffle that wiggles constantly and pick fights with it.

- Put the same horse in a full cheek eggbutt with no wiggle, and suddenly he chills—because the bit sits still unless you mean something.

A horse might prefer a stable bit over a pre-signal bit because:

- It’s quieter

- It’s more predictable

- It doesn’t nag or confuse

Lateral Pressure

Lateral pressure from the bit means side-to-side cues—where the bit presses against one side of the horse’s mouth or face when a rein is used. This helps signal turning, bending, or moving the shoulders over.

Different bits do this to different degrees:

- Loose ring snaffle = minimal lateral pressure (the ring moves independently)

- Full cheek or D-ring = direct lateral pressure (cheekpiece pushes against the face)

- Eggbutt = somewhere in the middle

Why Would a Horse Like Lateral Pressure?

1. Clearer Communication

Some horses—especially green, stiff, or bracy ones—benefit from literal, face-on feedback. A bit that pushes on their outside cheek (like a full cheek) makes it easier for them to understand:

“Hey, move your face this way.”

It’s like turning someone’s shoulders with your hand instead of asking them to guess.

2. Helps with Straightness & Steering

- Horses that drift through the outside shoulder or blow through turns get a physical barrier on their outside.

- Full cheeks support lateral control without needing a death grip on the outside rein.

Especially helpful for:

- Young horses

- Lesson horses

- Green riders

- Horses learning leg yields, turns on the forehand, etc.

3. Confidence and Predictability

Horses that are anxious or unsure may feel safer with something that gives consistent side contact.

Loose rings move around, twist, float. A horse who hates that “noise” in their mouth might love a fixed-cheek full cheek that says:

“The left side is here. The right side is here. The world makes sense.”

Science-y Bonus:

With a loose ring, the ring slides before the mouthpiece engages, meaning the lateral cue is delayed or softened (pre-signal!).

With a full cheek, there’s instantaneous, direct face pressure—like grabbing the outside door frame when you’re trying to steer.

Leverage in Bits

Leverage is about mechanical advantage — using the length of the cheekpiece to multiply the rider’s rein pressure so that the horse feels more force than what’s applied directly.

Think of it like a crowbar: the longer the bar, the less force you have to use to move something — but the more powerful the movement becomes at the other end.

How It Works in Horse Bits

A leverage bit has two points of attachment:

- Top — where the cheekpiece of the bridle attaches. Also known as the purchase.

- Bottom — where the reins attach. Also known as the shank.

When you pull the rein:

- The cheek rotates, pulling the headpiece down → applies poll pressure.

- The shank rotates → can apply curb chain pressure to the chin groove (if there is one).

- The mouthpiece rotates or compresses → changes pressure in the mouth (bars, tongue, lips).

The distance between these points determines how much your rein aid is multiplied.

Leverage Ratio

- 1:1 ratio (no shank length) → direct action (snaffle, no leverage).

- 2:1 or higher → mechanical advantage — the horse feels more than you put in.

- Example: If a 4″ shank creates a 2:1 ratio, 1 lb of rein pressure = 2 lbs of force at the horse’s mouth/poll/chin.

- Longer shank = more leverage (and usually slower, more exaggerated signal).

- Shorter shank = less leverage (quicker signal, less force multiplication).

Effects of Leverage

A leverage bit can:

- Increase poll pressure (encouraging lower head carriage).

- Increase chin groove pressure via curb chain (discouraging the horse from pushing against the bit).

- Sometimes create more mouth compression depending on mouthpiece.

It does not automatically mean “harsher” — it’s the rider’s hands + leverage ratio + curb setup that decide how strong it feels.

What Bits Really Do: Inside the Mouth – Pressure Points & Sensitivities

Now, inside the mouth, the bit interacts with:

– The **tongue** – very sensitive, especially to compression

– The **bars** – the toothless gap between incisors and molars; a common contact point

– The **palate** – roof of the mouth; often irritated by single-jointed bits or high ports

– The **lips** – which can be pinched with loose rings or poorly fitted bits

Outside the mouth

-The chin groove – Curb chains apply pressure here, preventing curbs from over rotating in the mouth and squeezing the chin

– The poll- Pressure applied here from curb bits ask the horse to lower their head

-The nose- used in bitless bridles. Pressure on the nose and face gives the horse information on steering and stopping.

Different horses have different mouth conformation: thick tongues, shallow palates, or low bars. One bit does not fit all.

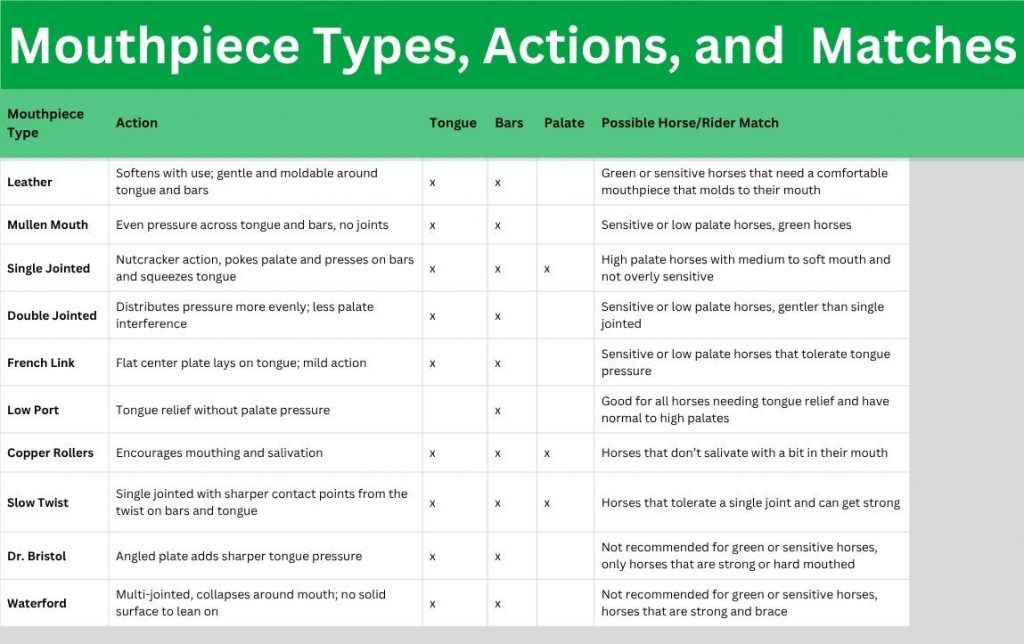

Understanding Mouthpieces: Types, Actions, and Horse Suitability

Choosing the right bit mouthpiece is like picking the perfect pair of shoes — the wrong fit can cause discomfort, resistance, or even pain, while the right one supports comfort, communication, and performance. Below, we’ll break down the most common mouthpiece types, how they act in the horse’s mouth, and which horses they tend to suit best.

Leather Mouthpiece

Softens with use, becoming gentle and moldable around the tongue and bars.

Action: Gentle, flexible, and forgiving.

Best For: Green or sensitive horses that need a comfortable mouthpiece which molds to their mouth for a custom feel.

Mullen Mouth

A solid, curved bar that applies even pressure across the tongue and bars without joints.

Action: Steady, consistent contact without a nutcracker effect.

Best For: Sensitive or low-palate horses, and green horses who benefit from stability.

Single Joint

The classic “nutcracker” action — folds in the middle, pressing into the bars, poking the palate, and squeezing the tongue.

Action: More direct and sharper than a mullen, can put pressure on the palate.

Best For: Horses with a higher palate and a medium-to-soft mouth, but not overly sensitive.

Double Joint

Two joints create a softer, more even distribution of pressure, reducing palate interference.

Action: Wraps around the tongue and bars more evenly than a single joint.

Best For: Sensitive or low-palate horses who need a gentler feel than a single joint.

French Link

Features a flat center plate that rests on the tongue.

Action: Mild and even, less nutcracker effect than a single joint.

Best For: Sensitive or low-palate horses that tolerate tongue pressure.

Low Port

A slight curve in the center that offers tongue relief without pressing on the palate.

Action: Creates space for the tongue while keeping contact on the bars.

Best For: Any horse needing tongue relief, especially with a normal to high palate.

Copper Rollers

Beads or rollers that encourage movement of the bit in the mouth.

Action: Encourages mouthing and salivation, can add some distraction for busy mouths.

Best For: Horses that don’t salivate much or need encouragement to soften in the mouth.

Slow Twist

A single-jointed bit with twisted metal along the mouthpiece for a sharper feel.

Action: More intense bar and tongue pressure due to the twist edges.

Best For: Horses that tolerate a single joint and have a tendency to get strong — not for sensitive mouths.

Dr. Bristol

A double-jointed bit with an angled center plate that applies sharper tongue pressure.

Action: The angled plate increases intensity, especially under contact.

Best For: Strong or hard-mouthed horses — not recommended for green or sensitive types.

Waterford

A series of ball-like joints that collapse in all directions.

Action: No solid surface to lean on, moves constantly in the mouth.

Best For: Strong, bracey horses — not suitable for sensitive or inexperienced horses.

Final Thoughts

The mouthpiece you choose should match your horse’s palate shape, tongue thickness, sensitivity, and level of training. A gentle, stable bit can build confidence, while a more complex or stronger bit may help refine control — but only in skilled hands.